LAB 4/22/17

Saturday, April 22 at 1:30pm

with The Blow (Melissa Dyne and Khaela Maricich), Tristan Perich, Aki Sasamoto & Tina Satter.

moderated collectively

The Kitchen L.A.B. Conference also included several works commissioned throughout the year from Half Straddle, The Blow, Tristan Perich, and Aki Sasamoto. Using their work at The Kitchen as a starting point, these artists discussed the nature of their positioning of the audience, and how that relationship is connected to the architecture of the performance space.

Tristan Perich’s work is inspired by the aesthetic simplicity of math, physics and code. The WIRE Magazine describes his compositions as “an austere meeting of electronic and organic.” 1-Bit Music, his 2004 release, was the first album ever released as a microchip, programmed to synthesize his electronic composition live. On March 17–18, 2017, The Kitchen presented “Tristan Perich: Five Works,” two evenings of compositions by Perich, including a number of premieres featuring renowned performers and ensembles including Dither, ACME, Mariel Roberts, Sō Percussion, JACK Quartet, and DUOX88 (Vicky Chow and Saskia Langhoorn).

Aki Sasamoto works in sculpture, performance, and storytelling. In her installation and performance works, Aki moves and talks inside careful arrangements of sculptural objects, weaving together mathematical principles and the bizarre emotions behind daily life. In her exhibition Yield Point, on view at The Kitchen April 6–May 13, 2017, she put up bags with static electricity, stretched trampolines, sliced and reassembled dumpsters, and filmed the universal testing machine used to test tensile strength at the Engineering Department where she teaches Art. The installation explored the need for sufficient elasticity in life. How close can one approach one’s breaking point, and what happens between one’s limit and one’s end?

Tina Satter is a writer, director, and Artistic Director of the Brooklyn-based, Obie-winning theater company Half Straddle. On March 8–18, 2017, The Kitchen presented Half Straddle’s Here I Go, pt. 2 of You, an open work period and colloquy that encompassed rehearsals and showings of new theater and video work; the launch of an online journal of performance writing; public lectures; communal zine-making activities; and discussion periods. A reclamation of space, ideas, and paradigms by female-identified and informed bodies and queer bodies embodying feminist ethos, Here I Go, pt. 2 of You engaged company members, peers, and their artistic heroes to expand critical artistic discourse to interrogate and reflect on how we codify; and to consider why various performances are made and ask what their making means at this time.

The Blow is Melissa Dyne and Khaela Maricich, a shape-shifting entity of varying forms that employs popular music as a vehicle for broader explorations. Operating between contexts and genres, the duo works with sound recording, performance, installation, writing and physical media, aiming to address and expand the limitations encountered within each framework. On March 30 and April 1 at The Kitchen, The Blow premiered their latest material in Brand New Abyss, a unique performance environment for electroacoustic sounds woven out of frequencies and pop songs.

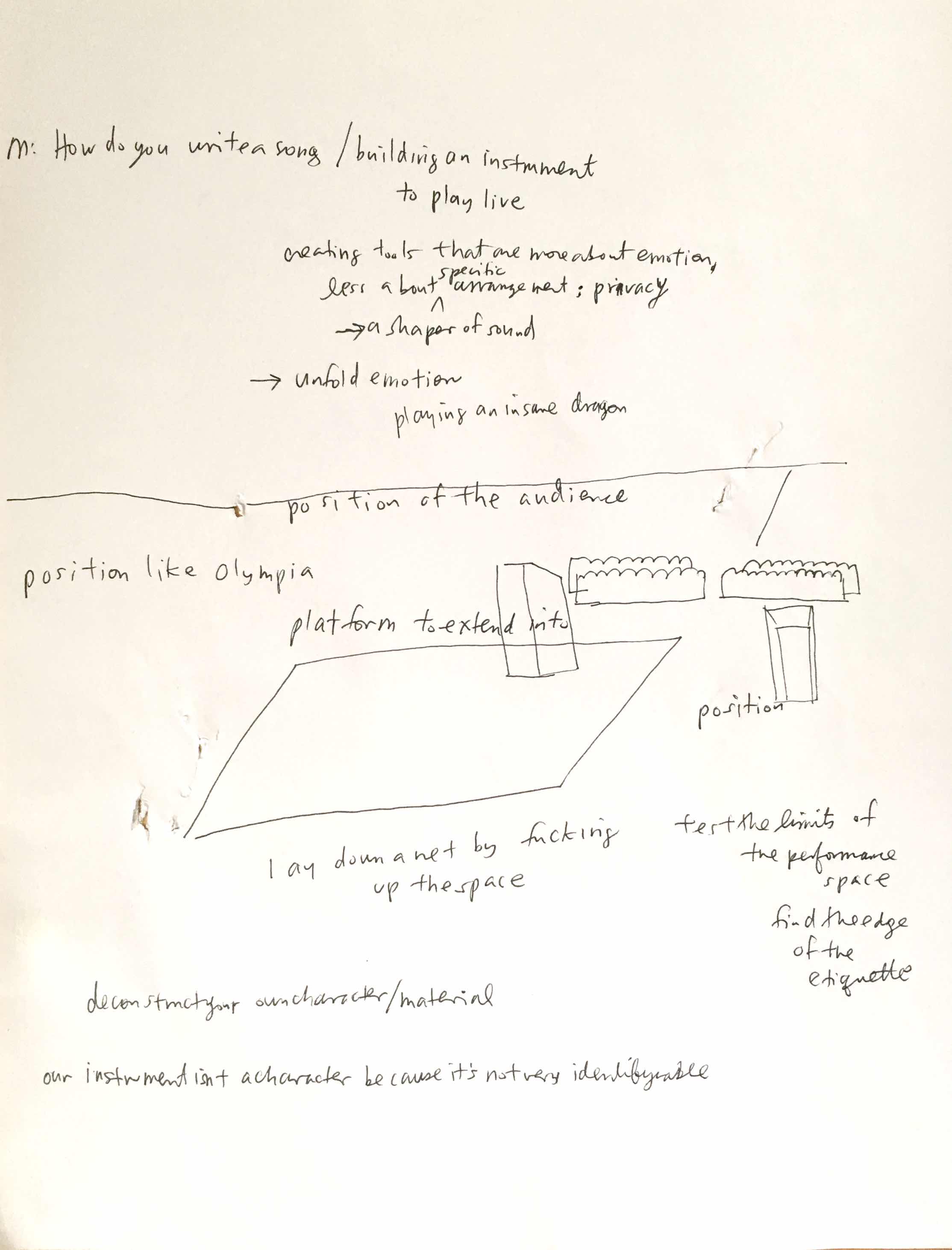

Aki Sasamoto’s notes in preparation for her discussion at The Kitchen L.A.B. Conference: Position.

TRISTAN PERICH

I think position relates to my work in two particular ways. First, there’s a literal, geometric, more tangible experience of position in my performances as they happen on the stage, involving instruments and the way I work with electronics—which is just a matter of bodies and instruments in space. It’s a very simple idea, but it’s something that is part of every piece of music: every instrument makes sound, and sound is grounded in space, so there’s a position and direction to sound, and therefore to any performance. The same is true of electronic sound. We don’t think about it as much when we listen to music on our headphones—where the sound is sort of position-less, piped directly into our brains—or when we’re in a venue where the lights go down and the speakers are hidden and you’re not aware of the sound source. But electronic sound, of course, comes from speakers, just as any sound comes from a source. And that fact has been quite inspiring to me when I compose music, and then in other media.

A second sense of position relates to the foundations of the world around us—basically in the realm of quantum mechanics and, more plainly said, with respect to the position of information. In quantum mechanics, there are fundamental particles like electrons and protons, which are made–up quarks; and each of these particles has basic states, like the spin and other values. Anytime these particles interact, it’s as a kind of information moving through space, with information interacting with other information. In this respect, the “position” of information might recall the headphone example I used: When we use the Internet, we think of information as this sort of omnipresent thing that you just take out of the cloud and show on your screen. But there’s a sense of universality to it, because it’s so readily available; the speed of light is so fast that it brings information to us so quickly, and that information is stored on so many servers around the world that there’s a redundancy. And so you don’t know where it’s coming from at any moment in time. Politically, this question is getting more and more important, because you have different governments accessing servers within the U.S., trafficking information between our country and others. Still, the idea of information as a physical presence, and as having a physical position, has been very inspirational to me—even though I work with it as abstract, because sound isn’t a fundamental particle but instead a massive number of air particles moving with a changing pressure that we then hear as sound. In other words, what I’m interested in is a more generalized idea of the intersection between the physical world around us, the world that we can relate to and understand, and the abstract world of electronics.

One could illustrate this, perhaps, by looking at the difference between the first instrument I ever played—the piano—and a raw speaker cone that I’ve used more recently [Perich points to image of himself with cone onscreen]. They’re different, but also the same in many ways, because sound is a physical process. And so I explore this in works that are purely electronic—with an album of electronic music that I released as a physical object that you plug in and you listen to, for example—or that consist of performances with musicians onstage alongside these electronics. I think about different categories of instruments, the different ways they make sound, and then about what electronic sound has to say in conjunction with acoustic sound. For instance, if electronic sound is generated by code, how does code relate to the score that the musician is playing? And I find this to be a very cyclical exploration. When I think about code, it informs my writing for acoustic instruments; and as I write a new piece for different acoustic instruments that informs my thinking about code.

For instance, I wrote a piece for piano and forty speakers, which led to a much more reduced piece that I presented at The Kitchen last month for two pianos and two speakers. (Although in this case I was starting to work with much, much larger speakers.) Let me just play you a quick excerpt of that work, titled Sequential. [Perich plays selection.] On the second night of those performances, I presented another work for eight musicians—a string quartet and four percussionists—in which everybody is bowing their instruments very, very quietly. In this case, instead of working with speakers plugged into my electronics on a sort of 1-bit, basic binary level, I used 1-bit signals at a much different pace to cut the signal of the eight musicians in and out. It’s basically a system of gated electronics, or gated amplification. You’re hearing all of the sound from the instruments, but it’s being just turned on and off by the electronics in kind of a rhythmic score. [Perich plays another selection.]

So you get the idea. But to make it that much more concrete, I have one of the boards from that performance here, along with four microphones routed into it. I’m going to surprise the people who are sitting in front of these microphones, asking them to make a continuous sound, which could be a simple tone like this. [Perich sings tone.] I’m going to turn on the circuit board, which will allow us to hear the piece—although with the wrong notes, I guess. Let’s begin. [Participants sing piece.]

Thank you, everybody, for making the sound. It was wonderful. So, here again, you get the idea. There’s something positional there. And maybe what’s worth saying is that I wrote that piece for my show here, in response to my works being performed in larger spaces, where I’m not finding myself able to present just an acoustic performance anymore. It’s like I’ve had to engage the sound system of venues by necessity. And so this became a piece in which I tried to use the sound system in a meaningful way, to kind of “reposition” the sound source from the musicians onstage into the space.

Finally, I’ll just mention that I’ve explored these ideas in other media—for instance, in drawings made by machine, which are kinds of exploration of space through randomness and order. Similarly, I’ve made 1-bit video, which is very, very basic, digital signals that create these black–and–white images on TVs, which is interesting because TVs, like speakers, are these wonderfully direct mechanisms for turning a signal into an output of some kind. Basically, I’ve thought of TVs as positional in the same way that the speakers are. In turn, I’ve started working with dance, choreographing for televisions onstage with dancers, cutting the power cords to the TVs and putting batteries inside them along with circuit boards that synthesize the video, so they become building blocks of a sort. And they create the light for the piece too, so, projecting light in the way that speakers might project sound. It becomes another kind of source.

The Blow’s notes in preparation for her discussion at The Kitchen L.A.B. Conference: Position.

TINA SATTER

Poison the Position

I’m going to start with reading from a talk that the writer and actor Jess Barbagallo gave at our project we did here at the Kitchen in March called Here I go, pt. 2 of You. This is from the first of two lectures Jess delivered as part of that. This lecture by Jess was called “The Burden of Identity: I Prefer Not To.”

Jess says:

“Tina was calling her event “Here We Go, Part 2.” Part 1 was the more insular affair Half Straddle hosted at Dixon Place in 2012. It was an emotional reckoning (Tina’s) that turned into an art manifesto which she titled “Quantifying the Reasons We Still Make and Need Live Art.” I revisited this manifesto in preparation to speak to you tonight and I found a line, this line I like best. Tina writes “I don’t want to make the opposite of what I want to make.” For me, it’s a nice point of departure as I crisscross the implications of that sentiment with other private conversations I’ve had in my life, the ones that highlight the ever ongoing tension between the split obligations a person has to the world and to the self.”

And Jess continues:

“The artist Tania Bruguera, sums up this emotional-political complex as ‘living the fragile balance between ethics and desire.’”

I think that “between” position—the balance between ethics and desire—is a really important version of articulating “position” now in this moment in considerations of making art, how, and to what ends.

I didn’t hear that idea or have an articulation myself until the second night of our lecture series when Jess said it out loud and quoted Tania—but that idea—living, making, negotiating that fragile balance very much fuelled what I was trying to do with this project since I began working on it two years ago, and which I never quite knew exactly what I was doing because it’s so different than the usual shows and performances I make.

But, one thing that I always knew that I wanted to do with it, was to make a literal and idea space that held quivering positions, that held them up sharply or with a million questions inside, but all to clarify and complicate and totally call out that the time of position is now. And that was, at once, a totally selfish need I was trying to figure out for myself how to make happen with who and what I knew how to do, and was also about the idea of stepping back and hearing and seeing others, and not talking, not making.

I just want give a very quick overview of the project so people have context. It was a two-week installation and colloquy up in the Kitchen Gallery space called Here I Go, pt. 2 of you and the centerpiece of it was a free lecture series with people I asked to speak who I felt should be our current public intellectuals, and several of them already are. Each lecture was preceded and followed by a very short music performance by a range of different musicians, some of my regular collaborators, several were really young musicians I found through the Willie Mae Rock Camp for Girls. And the lecturers ranged from teenagers just starting to make performance to established public intellectuals like Sarah Schulman, and many amazing people in between. And we designed the space specifically to hold all of this, and using elements from the company’s past work.

Here’s some image of the space so you also have some look and feel.

[Documentation Projected]

Information on the project is still on the Kitchen website so you can see the full list of speakers and the titles of their talks which were really great. But I do want to note here that Kitchen Curator Lumi Tan gave a excellent talk as part of it called "Being a Good Woman in the Art World."

At the L.A.B. talk this past Thursday, the artist Mariam Ghani paraphrased Sarah Ahmed at one point to say that “Stating a position is non-performative, it doesn’t do anything.” And I immediately scrawled that down because a really important part of my project was that although many of the people speaking are excellent performers and artists, I specifically wanted all of these people to just speak, to not perform, to very clearly frame them as people we should listen to in this moment. They were stating positions.

Another impetus for this project had been to carve out into the air for the kind of discourse and thought and criticism I feel is missing around the kind of work I like to see and make, and instead of continuing to just complain about it, why don’t I try to put some of it out there. And Mariam and Chitra Ganesh also spoke on Wednesday about a project they collaborated on which they said was in part to create “the critical discourse in which they wanted their work to be seen.”

This is an expanding, an excavating, a complicating of position that clearly many of us crave.

Ariel Goldberg, writer and artist, gave a talk as part of our project drawn largely from their book, “The Estrangement Principle.” I can’t recommend this book enough and it totally grapples in personal and intellectual ways with concepts of position. I’m going to read this excerpt from it that’s on the back of the book.

Ariel writes:

“I began collecting the phrase ‘queer art’ in all its sweaty megaphone pronouncements. I felt pricked by ‘queer art’ which I heard being uttered all around me in the titles of group shows, dance parties, anthologies, mission statements, press releases. I was also collecting palpable silences around events that could have used the word ‘queer,’ but didn’t. I had to get close to this description, like I get close to frames in museums, breathe on their glass and notice the dust. I wanted to get so close my vision would blur.”

I went back to Rel’s talk and their book in preparation for today, and in the book was looking for any instance of the actual word “position” and came upon a this epigraph to a chapter:

“Help us poison position.”

This is from a poem by the poet and activist Dawn Lundy Martin.

Theatermaker Kaneza Schaal spoke here also in the L.A.B. talk on Wedsnesday about the need to kill the zombies that remain entrenched in unchanging positions. Poison feels close to that.

Because I like weird fairytales, and creepy stories told in girls’ bedrooms, and poisonings that could actually be kind of exciting and necessary, it was that kind of super stark poisoning I was seeking—to deal with my own shame and questions and confusion and desire to dig deeper and better around my positions, the position of a theater company, the position of making art, the position of my privilege, where do you put one’s position. It has to go somewhere.

The playwright Jeremy O. Harris worked on excavating the shards of position in his talk when he spoke about his mom coming to New York City recently to see his work live for the first time, and she texts him to ask, “What is the dress code for a play reading?”

In her lecture at Here I Go, pt. 2 of You, the actor Emily Davis discussed her brother’s ongoing drawing and painting practice after he’s had a brain injury at age 12. She said something that I return to in relation to the slipperiness of position and the attempts to know and wrangle it.

Emily says:

"Who or what do I love, what am I curious about, and how do I get closer to that thing, today, when it can feel so far away? When I don’t have the words that we’ve agreed are the words?”

Emily also says:

“A family might, in solidarity, decide that what is perceived as a disability could instead be something that rips at the seams of banality. It’s a silent agreement. This shift is so inevitable, so programmed into our human-beingness that it is impossible to stave off.

Our natural inclination is to move toward light. Learning is hard, a radical unlearning is harder.”

And, finally, to end with another section from Jess Barbagallo’s talk:

Jess says:

“My mentor and friend Cecilia Gentili says I must show up and be an example for those who have been scared into hiding so I meet with young genderqueers in coffee shops. They want to know how it is I can have this identity and be a performer, make art. I patiently explain my luck; the privileges of my geography, education, race; the self-doubt that never goes away. I don’t tell them that I am vaguely estranged from my parents and I can’t fully articulate the pride I take in having become a fine physical actor, despite all the years sweating in binders, layered up in the studio while so many cis folks flirted in their proud bodies. Sometimes I even sensed my difference was a real pleasure to them, to have me in their room which was rarely my room, thanks for coming, that breath of fresh air everyone needed from the demands of hetero and gender normativity. I suppose this special status was meant to sustain me. I want to not succumb to an ageist script by telling these teens and twenty-somethings what makes most sense to me: you must be tougher. So I put my hand on the wooden table and say: tell me what you want to make.”

To me, that ultimately remains the statement on position that contains all its necessities and possibilities for the personal the political and all the sinew in between. Tell me what you want to make.

ROUNDTABLE DISCUSSION

Katy Dammers: Everyone here has spoken about how to position the audience, yet a question that remains for me is at what point do you make that endeavor explicit? Do you give a kind of warning, or do you move from one stage to another without signaling it?

Melissa Dyne: No warning.

Khaela Maricich: No warning at all. Life is no fun if you warn people. Although I guess one could say that’s what the larger world is like now, and we don’t want the world to be like that.

Tina Satter: If we’re talking about positioning the audience, something important I discovered in this L.A.B. when speaking with the playwright Casey Llewellyn and actor Jess Barbagallo arose around our relationship to the audience. Answering one question, Casey said, “I make my work totally thinking about the audience,” which made me realize on the spot how I make my work not caring about the audience at all. Or I do care for the audience. They’re there. I want to make it for them. In fact, something I learned from Richard Maxwell’s work is that you’re not trying to pretend in theater that you’re not there: you recognize you’re there, deciding that now we’re going to do our show. I’m in that school of having a beautiful curtain between us, but we all know you’re there. Yet after Casey spoke I was like, “Hmm, I’m going to have to think a lot more about what that means.”

Tristan Perich: When I think about audience, I like to make the relationships actually very explicit both between the audience and the performers, and between the performer and the composer. I think it’s to everybody’s benefit when the roles are really explicit.

But in terms of space and the position of an audience, part of that explicitness is for people to be aware of what’s happening in the same space that they’re in. I don’t like the stage to be an emulative experience. If there’s going to be a surprise, I want it to come from the music or from the content as opposed to the context. Actually, I really like to perform in gallery spaces, because the audience is really in the same space as the sound production, and they’re very aware of this. There’s no separation. Of course, galleries often have lesser sound than a theater. In this respect, The Kitchen is a strange space, because you kind of want to do something in each of the spaces, but you have to choose. It’s got such a great gallery, but then the sound is so good in the theater that it’s hard to walk away from.

Aki Sasamoto: I like explicitness, too, but it’s hard to settle on what that means given that the art I learned from was steeped in the deconstruction of tradition. When a tradition has been built on the idea of the unexpected, it’s difficult for people to grasp any tension between the expected and unexpected. In fact, for me, it’s hard to create a sense of the unexpected without creating something gimmicky—a sense of something “expected,” which I can work against. So I have to make sure I have an audience in mind when I perform; it helps me notice gimmicks, which I can edit out on the spot. But it’s all the more difficult because I can fall prey too quickly to this desire to establish something.

KM: Do you mean that you’ll set expectations so that there is something to deconstruct?

AS: Yes.

KM: That’s why we like working in a music context, because the expectations are so clear—and the limitations of the audience’s attention span are so clear—that there’s something really to push against. And when we come into a performance or art space, the rules are so unwritten that actually we just want to walk around in it. In a gallery there’s this openness and comfortable sense that I’m able to do stuff that I can’t do anywhere else, but it’s harder to deconstruct because it’s harder to figure out what the rules even are. In fact, in the performance space, it’s black, so you can’t actually tell where the walls end.

AS: That’s still a good space for me to work with, because audiences don’t know exactly what is going to happen. Or they don’t tell me what should happen. Then I can take that opportunity to go deeper into themes, and I’m free to quote from other things, switching, say, from talking to dancing, and it’s totally okay. I have to make sure that the quoting is not thin, true. But you can create a different type of audience here, because the audience will move with you.

MD: I did notice about that one show we did with two stages that people said it was like having divorced parents. They didn’t know where to look. It was confusing, and in the music context seemed to change the rules. In fact, because I was out in the audience, people started touching me, and I just had to accept that, even if it was a little creepy sometimes. We had changed the space and I said, “Well, we asked for it. We’re in it, and this is part of it.” It was an agreement, I guess.

KD: Tina, I wonder what you might say about that, because you’ve worked both in our theater and in our gallery space.

TS: In the theater, for me it becomes about technical things like sight lines, hearing the actors…all the “theater” things. But in the gallery, it quickly became clear that it wasn’t going to be a regular show; we weren’t using the space with a stage, although it did have a stage aspect. We tended to that space and made it ours, but I also was letting go of the sense of control I would normally have. People were going to walk in and use the space differently, and, for me, having someone say something in a staged dynamic without every second of the encounter planned goes against my usual direction of theater. Normally I’m trying to control every molecule of a production, and up there I was not doing that. It was this gallery space, and I just had to let myself play in it. It’s interesting how people would come and go in these free lectures—all things that would have literally given me anxiety attacks in theater. But the talks were incredible. It looked really beautiful. This weird pressure of the transaction was off, and it was very helpful, cool, and scary to experience that around something I had put as much time and work into as I would have making a regular show.

Audience Member: You’ve all kind of discussed position with respect to your audience and the space. But I’d be curious to know how these questions have changed for you now that everyone is attached to smartphones and interacting with everything in the world through that instrument. Are people less able to focus for any period of time, and has this created a different aspect in your performances?

TP: I don’t know if I have anything particularly interesting to say about that. Well, maybe the interesting thing is I’ve actually never really thought about that at all. As much as I think about it in the world—about technology and its influence on us, and our reliance on it, and our loss of agency as citizens through these ubiquitous devices that we don’t understand—I really don’t think about audience attention deficit disorder coming from them. Maybe it’s because I employ a traditional performance context. Although, I might add, I think there can be venues in which a successful performance is one where everybody has their cellphone out taking pictures.

KM: When we performed with Pauline Oliveros at National Sawdust in October, the success of that show was that nobody took their phones out. Everybody was utterly present. When something is really good, there’s no documentation, because everybody is actually there.

TP: I agree with you. Actually, someone I know does a performance that involves high-powered lasers, and he asks the audience not to take any pictures. It’s an electronic music crowd who would normally have them out the entire time, especially with this amazing visual, yet they’ve respected it.

KM: They’re forfeiting their future currency, where they can say, “I saw this.” They’ve agreed to just be in the present.

AS: If people are taking pictures, they are probably not engaged. Although our conversation makes me recall how I make my performances around twenty to thirty-five minutes, because that’s when people start to lose interest. This originally concerned me because I thought I was serving the audience even though I try to make work that’s supposedly not for the audience. Then I realized that it’s only my own stamina. I’m also a contemporary and perhaps I can’t sustain the interest so long, either.

But to return to the question of cameras, it’s also interesting to think of how people taking photographs and, say, being stopped can be a clear measure of what’s allowed. It might be a weird thing to say in today’s political context, but I feel like those are the moments when I see the borders of what’s allowed and what’s not, and I like those incidents.

KM: I’m reminded of living in Olympia, Washington, where there was a pretty radical performance scene through the 1980s and ’90s based on the idea that you could do whatever you wanted, and you didn’t have to be good at it—and there’s zero documentation of anything that happened, even when it comes to the good artists. There was a sense of freedom that was engendered by this lack of documentation, because you weren’t thinking of any dimension outside yourself. I think we were trying to invoke that sense of safety in our recent performance here. It was really small. There were only so many seats, and we were free to do something really fucked up, laying down this safety net, having totally different stakes.

Tim Griffin: Right or wrong, I’ve always presumed that art spaces are in dialogue with larger social structures, with the different protocols of spaces—and the confusion of them—lately mirroring confusion in the public sphere during the past couple of years. I guess my question in this context is: what do you find most useful to push back against right now? And if you’re not “pushing back” in an ambiguous sphere, what are you seeking to create, or what do you find yourself most interested in subsequent to the stage or gallery context?

AS: I think it’s a hard time to push against social structures, because I don’t trust my assumptions about them. I need time to slow down my understanding of contemporary circumstances. But I think this difficulty is also related to the fact that I learned art from people who deconstructed the tradition, so there is nothing in art for me to talk back to. I only have to go more internal. I feel a little bit embarrassed about this internal model, because it sounds so romantic when it’s paired up with art history, but that’s the only thing I can hold onto. Over and over, every time I make a project, the project makes me lonelier.

MD: I agree with you. For me, it’s about pushing back against myself—my own skills—and trying to scare myself into doing something without relying on conventions or history. I feel like we’re in this time right now where new things need to happen. I feel so many genres, like pop music, haven’t changed for thirty years. It’s the same thing, and everyone is really tired of it, but how do you make something new without referencing yourself? I think in the past you could turn to referencing your community, but now the community has really opened up. It’s been so globalized. So today we see people just trying to broaden something, trying to scare the crap out of themselves and get people to feel something new or different, even if it means you fail. I think it’s a time where failure should be okay and shouldn’t be looked at as a negative but instead as a positive, because that means that you learn something and then the next thing you do is going to be that crazier or better.

TP: I agree very much with what Aki was just saying. I feel like I’m very internalized these days when I’m creating. I’m just utterly confused when I think about my work in relationship to the world. There are things that trickle in, but I’m questioning a lot of assumptions that I have these days. And I feel like, just to get through—because it’s very difficult to be “creative” in our political context I’m kind of sticking to my guns and trusting my instincts. I have to see where that takes me.

Matthew Lyons: This leads me to think about something that Tina discussed, in another L.A.B. conversation, regarding our occupying a crossroads or border position today. In our current world, where there seems to be a lot of shakiness, and a kind of daily hallucinatory information coming toward us, how should one sustain that position in an artistic, or personal, way? How can one make a territory for oneself? Is it through a slippery narrative position? Or how long can we deal with the world as it is now before something flips in art toward a more obstinate approach?

AS: I guess the reason why I am more internalized is I don’t want to respond to the anxiety of the world. I don’t want to come to my art with either assumptions or doubts. Instead, I want to go back to before that kind of doubt comes and just pause it. I want to go back to that kind of high time of scientific hypothesis and just propose something. By putting forward a hypothesis, I’ve already made a truth. But this is only to say that I have to first anchor myself so that I’m in one place; and then I can stretch or do whatever. In my gallery show, the thing I’m thinking about is how material does stretch but also needs a point from which to pull. Even though the material might be moving, the framework is damn strong. I guess this makes me want to say as well that any institution like this place—or any art institution I like—should not look for a new look. I want an institution to be like a really old library. And if a space wants to be a library—a place steeped in intelligence—it has to dig deeper into itself.

KM: I feel like Melissa and I have noticed a stratification that arises through certain economic realities. The “position” people take is based on how they got to where they are. I remember how we came here from the West Coast as artists in our early thirties and found that everybody in the art world had aligned themselves with this or that graduate school. Everybody had a pedigree that was their access. So our economic strategy was to move with the music world: That was our point of access, our way of living and getting paid, as opposed to expecting to be graduate school professors. I feel like creating those kinds of sideways alternatives is something that we’ve been interested in trying—as opposed to individual artists being, like, “I got my opportunity and now I’m going to do my thing and maybe I’ll invite you to be a part of it, or maybe not.” We’re trying to find something that is other than the cultivation of your resume or your CV. I think this is like your series, Tina, where you brought together a conversation and even took it outside of anything that you could say you wrote or directed. It’s less about acclaim than about the potential for a connection. Which is why, for example, we did a “No Microphone” event here, which is literally a gathering of people without a microphone. It’s a vision to create this space for failure, I suppose—a space to try things that you don’t necessarily know are going to be good. New York has everything except that space. That space is the opposite of the “excellence” of New York. We’re all trying to survive and we have to live way out just to exist, and, to me, this seems like an interesting way to push back against assumptions about how it all should be working, and against the economy of it all.

TS: To answer your question, Matthew, and hopefully tie my thoughts back into what Khaela just said, even a year ago I was asking myself what kind of work I should make now. Or, how do you still make work? That’s obviously a known discussion at this point. But, personally, I decided I was going to keep making my work and, to boil it down really simply, put no more heteronormative things ever onstage. I told myself that I was going to keep doing that, because that definitely needs to happen. Even so, I have truly questioned myself. On the one hand, I have this internalized aspect: I’m going to keep making things, and I’m going to keep the principles that are important to me, and see how I can make work that is even more meaningful and adaptive to what is necessary to be seen. But on the other, I feel less sure of what the big thing should be. I do know theater artists who have pushed against institutions, but I won’t talk about that right now because I feel less sure of what I’m going to make. I have to keep figuring that out. I don’t doubt my value as a maker, but mostly I am interested in who I can share this space with, and who I work with. I guess it’s the very position of questioning and reforming—the conversation—that seems like the thing right now.

TP: That just made me wonder whether the big thing we’re striving toward—this changing of the world—is impossible. In other words, the fact that suddenly we all feel like we’re supposed to be doing that is a problem. There is supposed to be some healthy balance between doing what we believe in and thinking about how it relates to culture as a whole. We shouldn’t feel burdened by the question of whether we should be thinking bigger, directly addressing these issues that weren’t part of our work before—or that were only one part of a plurality of things, whereas now suddenly our concerns are so heavily weighted toward the big thing.

TS: Yeah. I’m not concerned with that idea of fixing the big thing. But I will say that I don’t know what the shape of my work or shows should be now. It’s less a question of content—the content will probably be the content—than of what things should look and feel like.

ML: The Blow’s recent show at The Kitchen was called “Brand New Abyss,” which actually struck me about halfway through the experience—at which point I realized the show was meant for me to be in this space with you guys, with the feeling that the bottom was dropping out beneath me.

KM: That was our special gift to the audience. It wasn’t like we were trying to solve the world’s problems. We were just, like, “Here you go.” This is what it’s like for us right now.